Emilia Martin

I saw a tree bearing stones in the place of apples and pears

Dates + Events

November Pictura Kids with Emilia Martin

Saturday, November 8 | 11:00am - 12:00pm

November Gallery Walk Opening Reception: Emilia Martin

Friday, November 7 | 5:00pm - 8:00pm

Emilia Martin

I saw a tree bearing stones in the place of apples and pears

“In the Catholic church there are three classes of relics.

The first class is body parts of a saint.The second class is things that belonged to a saint, objects they have used and surrounded themselves with. The third class relic is the object that touched the body of a saint. To create the third class relics, the small holes are drilled in the tombs of saints. The objects are lowered through the holes, and once they touch the corpse they are no longer everyday and mundane – they now become sacred”

I carefully read through countless myths and tales on meteorites from around the globe, some too old to trace their sources back. There are stories about how cosmic rocks were sent by angered gods or satan, stories on how some were chained to the ground out of fear that they may return to heavens in the same way, they came to Earth. I read that a meteorite was powdered and consumed by those who witnessed its arrival based on the belief that it was a medicine sent from heavens. Some of those cosmic rocks took on central roles in the communities becoming places of worship, grief, sacrifice.

Despite these countless stories and myths, modern Western science has only acknowledged the meteorites as a scientific fact in the late 18th century, dismissing centuries of the countless reports as fictional fables, created by native communities or people like my ancestors - peasants, working long hours under the bare skies.

The meteorites do not only close the gap between the outer space and our familiar Earthly surroundings, but also transgress what is seen as ordinary and sacred, what is seen as mythical and true.

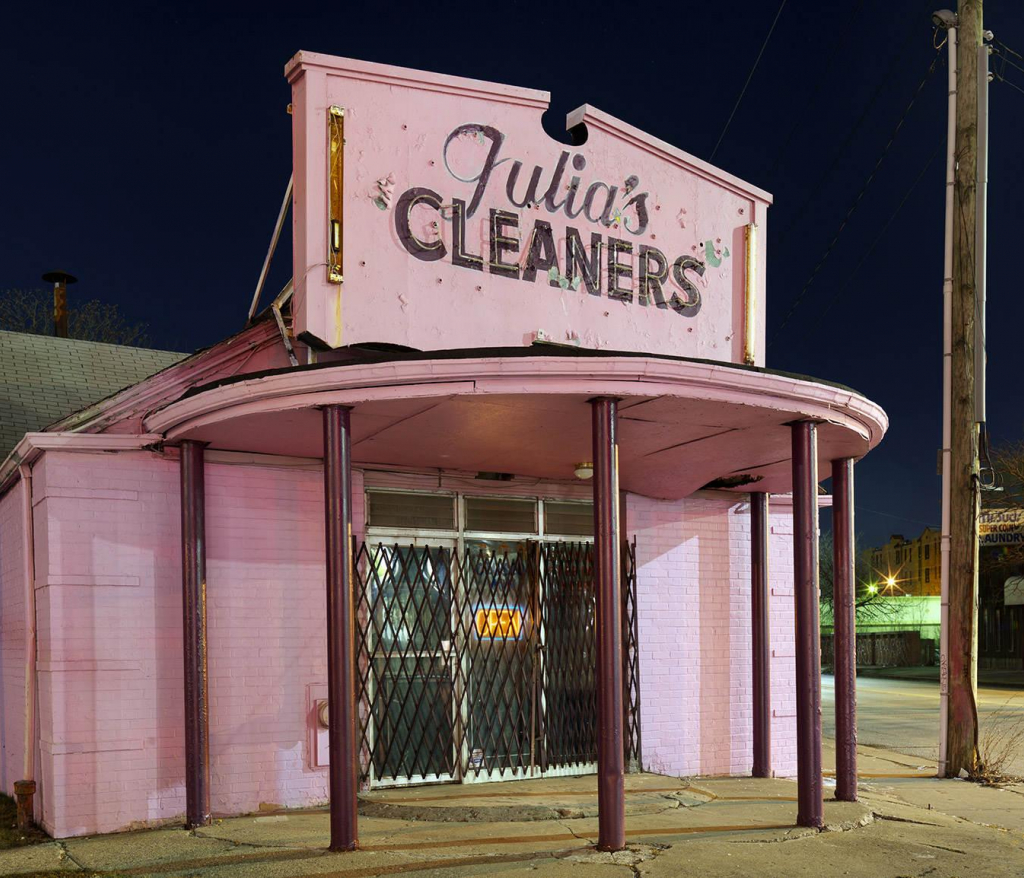

I saw a tree bearing stones in the place of apples and pears is an exploration of a rock as a carrier of stories, a migratory body, a silent, mysterious visitor, filled with projections and dreams. It is an exploration on who, throughout the histories, had the right to claim the truths and who - tales. It is a story on how some truths can only live subversively through myths and tales, away from the dominant narratives. It is a fantasy in which a rock - a symbol of muteness and inability to express, finds its voice and speaks thousands of stories, in the act of reclaiming them back.

(1) Sarah Sentilles “draw your weapons” Random House 2017

Emilia Martin (1991) is a Polish artist and photographer based in the Hague, the Netherlands, where in 2022 she graduated from Photography & Society Masters at the Royal Academy of the Art. Working with photography, writing, and sound, she explores how the stories we tell shape the realities we inhabit. Her process is based on careful research and personal, often playful approaches, through which she questions dominant narratives.Her work has received multiple awards and has been exhibited internationally, with the Rencontres d’Arles, Fotofestiwal Łódź 2025, and Photo Museum Ireland, among others. I saw a tree bearing stones in the place of apples and pears was published as a book in 2024 by Yogurt Editions and received international acclaim. It was one of the winners of Lucie Foundation Award, Fotofabrica Photo Book Prize, and Belfast photography festival.

www.emiliamartin.com

Emilia Martin takes the fact of the matter -burning rocks do sometimes fall from space, and leans into its strangeness. Scientists do the work to explain the phenomenon in intricate detail. But even a satisfying explanation does not temper the great strangeness. Intimacy with something so marvelous, so different from ourselves, needs more space to fully bloom.

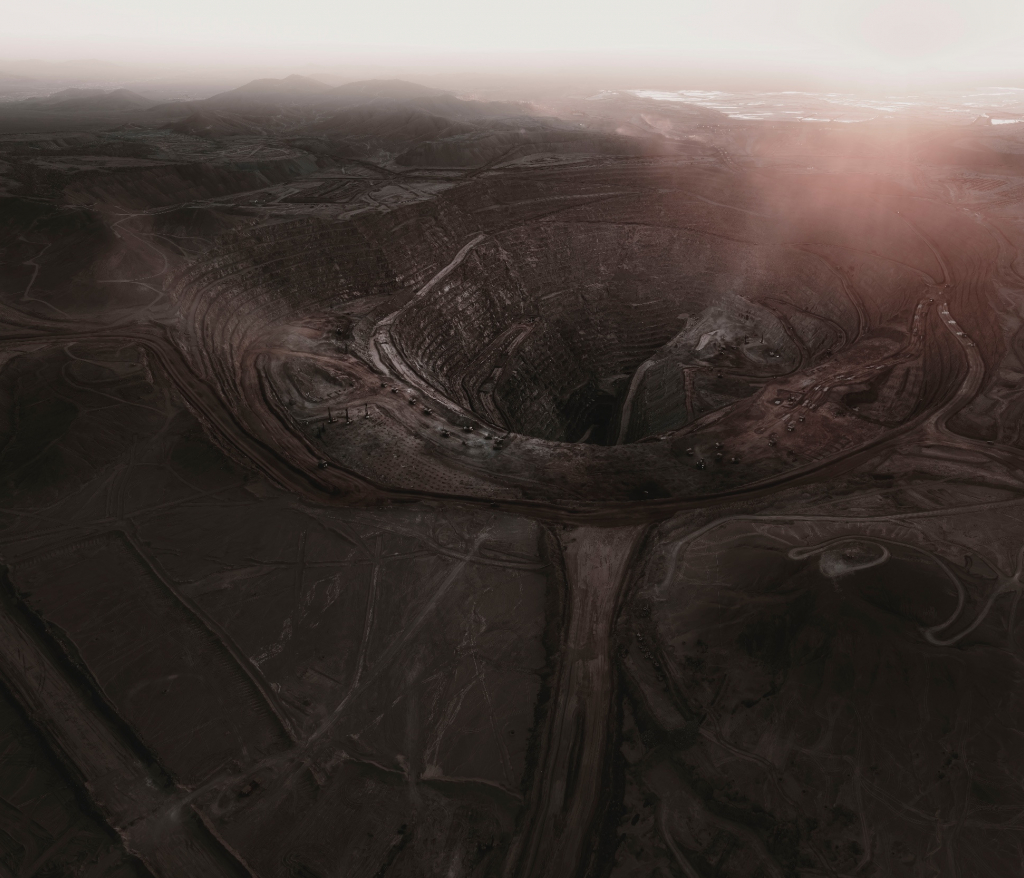

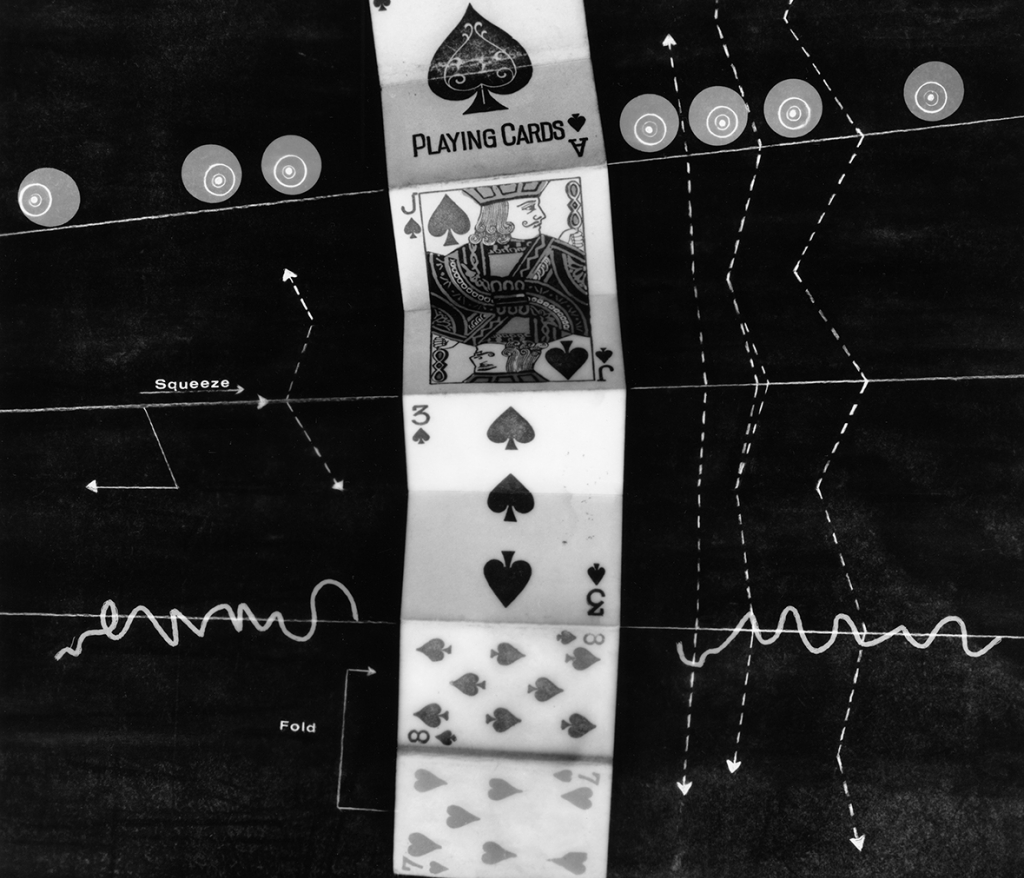

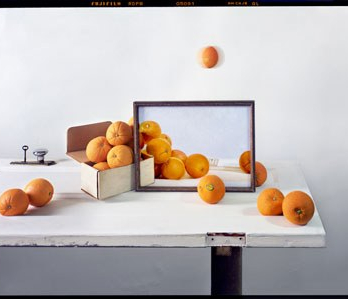

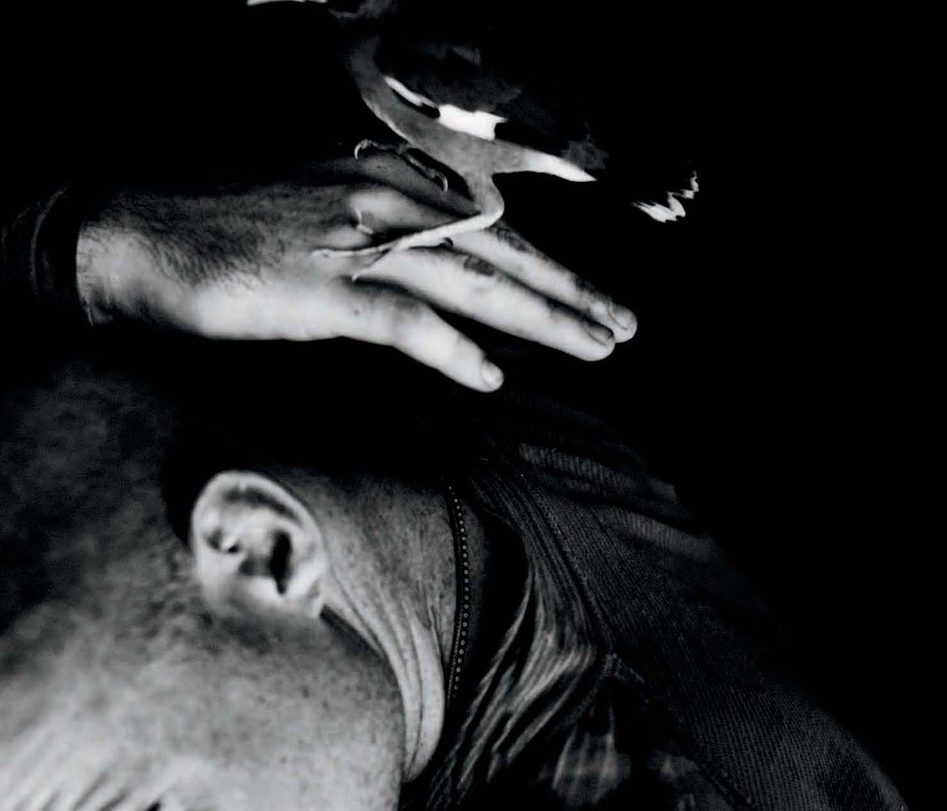

In building this body of work, Martin considers several different perspectives on meteorites, most notably, the point of view of the rocks themselves. She plays with the many ways they could interact with the earth. Acts of falling, hovering, being caught, protected, and cradled, all give a spark of animation to an object we typically consider to be mute and immobile.

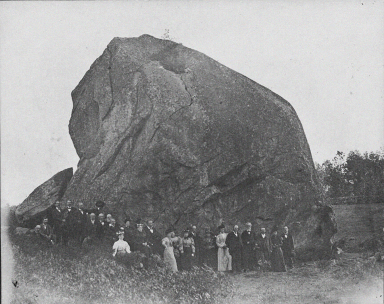

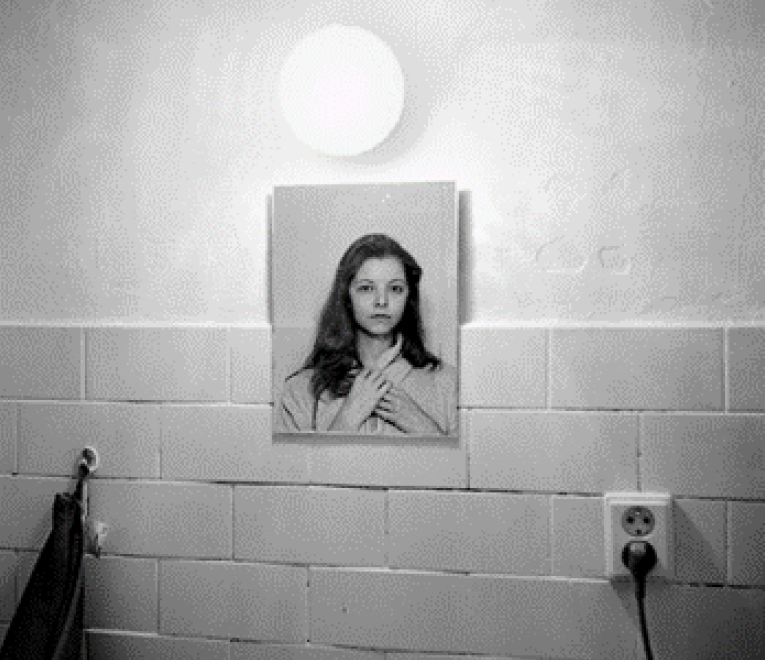

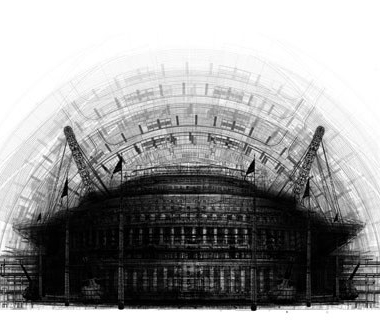

In an attempt to get closer, Martin places the human body against a rockface, allowing its perspective to be heard and absorbed. Mixing soft flesh with hard stone is a bit like trying to mix oil and water. It is an unlikely communion, but Martin is a natural mediator. The artist seems to sleep and dream on the rough surface, her braid draped softly on the ledge like it’s a pillow. Another image shows a stone about the height of a person, with a circular hole in its center. One human arm protrudes through and the other wraps around, so that the rock is fully embraced.

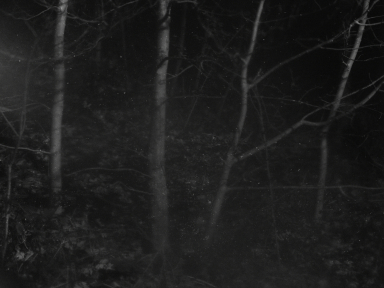

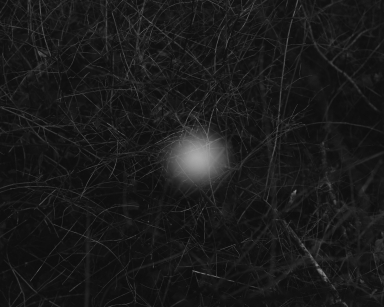

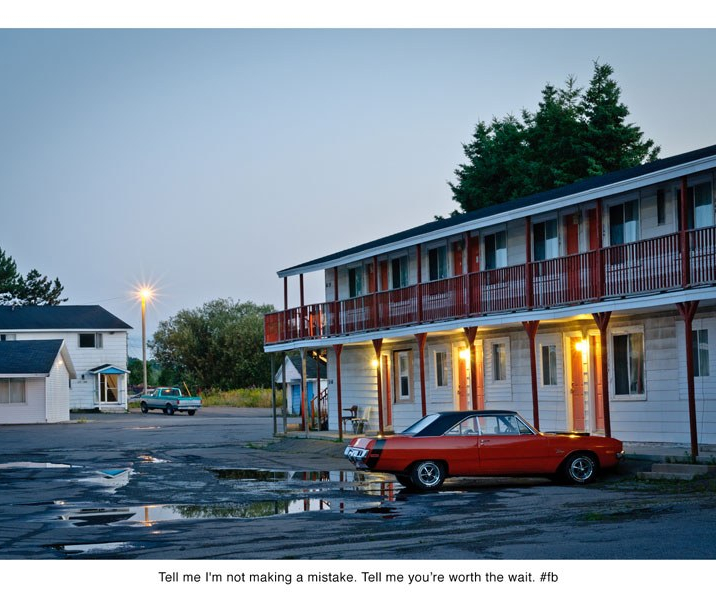

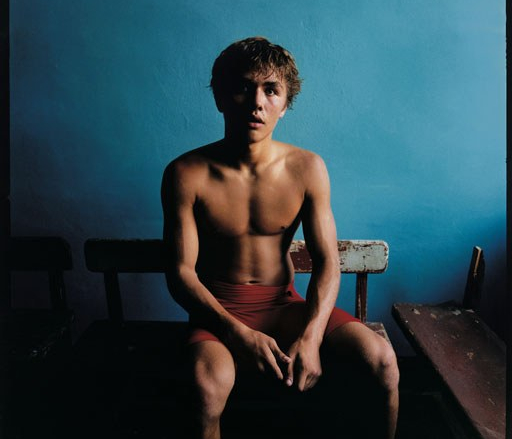

With poetic imagination, Martin creates an enchanting landscape for the meteorites’ journey. In the world on the walls, peasant women emerge from a dark forest. An orb of light hovers in a thicket, with an empty crater nearby. We begin to see the life and migration of the extraterrestrial visitors.

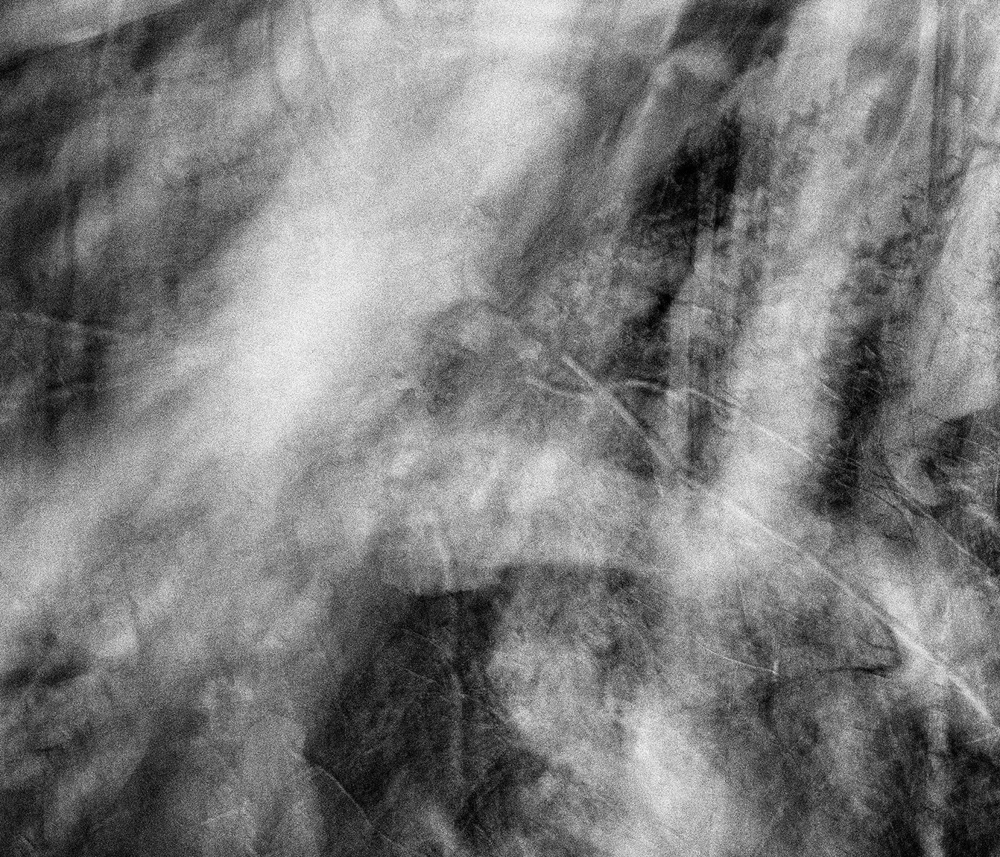

The photographs are printed on the darker end of the tonal range, so that when light appears, it’s glowing. Large swaths of open darkness are not to be feared; there is delicacy to be found in the shadows.

Early accounts of meteorites were dismissed as superstition, as if believing in the rocks was like believing in magic. But why shouldn’t they be magic? Even if and when completely explained, are they not still a bit miraculous? In this work, there is a playful yet intentional comingling of truth and tales, with a reminder that not all tales are untrue. There is tenderness in Martin’s approach that comes from the act of careful listening- she is listening to the old tales told in small towns, she is listening to scientists, she even listens to the rocks themselves.

Emilia Martin

I saw a tree bearing stones in the place of apples and pears

“In the Catholic church there are three classes of relics.

The first class is body parts of a saint.The second class is things that belonged to a saint, objects they have used and surrounded themselves with. The third class relic is the object that touched the body of a saint. To create the third class relics, the small holes are drilled in the tombs of saints. The objects are lowered through the holes, and once they touch the corpse they are no longer everyday and mundane – they now become sacred”

I carefully read through countless myths and tales on meteorites from around the globe, some too old to trace their sources back. There are stories about how cosmic rocks were sent by angered gods or satan, stories on how some were chained to the ground out of fear that they may return to heavens in the same way, they came to Earth. I read that a meteorite was powdered and consumed by those who witnessed its arrival based on the belief that it was a medicine sent from heavens. Some of those cosmic rocks took on central roles in the communities becoming places of worship, grief, sacrifice.

Despite these countless stories and myths, modern Western science has only acknowledged the meteorites as a scientific fact in the late 18th century, dismissing centuries of the countless reports as fictional fables, created by native communities or people like my ancestors - peasants, working long hours under the bare skies.

The meteorites do not only close the gap between the outer space and our familiar Earthly surroundings, but also transgress what is seen as ordinary and sacred, what is seen as mythical and true.

I saw a tree bearing stones in the place of apples and pears is an exploration of a rock as a carrier of stories, a migratory body, a silent, mysterious visitor, filled with projections and dreams. It is an exploration on who, throughout the histories, had the right to claim the truths and who - tales. It is a story on how some truths can only live subversively through myths and tales, away from the dominant narratives. It is a fantasy in which a rock - a symbol of muteness and inability to express, finds its voice and speaks thousands of stories, in the act of reclaiming them back.

(1) Sarah Sentilles “draw your weapons” Random House 2017

Emilia Martin (1991) is a Polish artist and photographer based in the Hague, the Netherlands, where in 2022 she graduated from Photography & Society Masters at the Royal Academy of the Art. Working with photography, writing, and sound, she explores how the stories we tell shape the realities we inhabit. Her process is based on careful research and personal, often playful approaches, through which she questions dominant narratives.Her work has received multiple awards and has been exhibited internationally, with the Rencontres d’Arles, Fotofestiwal Łódź 2025, and Photo Museum Ireland, among others. I saw a tree bearing stones in the place of apples and pears was published as a book in 2024 by Yogurt Editions and received international acclaim. It was one of the winners of Lucie Foundation Award, Fotofabrica Photo Book Prize, and Belfast photography festival.

www.emiliamartin.com

Emilia Martin takes the fact of the matter -burning rocks do sometimes fall from space, and leans into its strangeness. Scientists do the work to explain the phenomenon in intricate detail. But even a satisfying explanation does not temper the great strangeness. Intimacy with something so marvelous, so different from ourselves, needs more space to fully bloom.

In building this body of work, Martin considers several different perspectives on meteorites, most notably, the point of view of the rocks themselves. She plays with the many ways they could interact with the earth. Acts of falling, hovering, being caught, protected, and cradled, all give a spark of animation to an object we typically consider to be mute and immobile.

In an attempt to get closer, Martin places the human body against a rockface, allowing its perspective to be heard and absorbed. Mixing soft flesh with hard stone is a bit like trying to mix oil and water. It is an unlikely communion, but Martin is a natural mediator. The artist seems to sleep and dream on the rough surface, her braid draped softly on the ledge like it’s a pillow. Another image shows a stone about the height of a person, with a circular hole in its center. One human arm protrudes through and the other wraps around, so that the rock is fully embraced.

With poetic imagination, Martin creates an enchanting landscape for the meteorites’ journey. In the world on the walls, peasant women emerge from a dark forest. An orb of light hovers in a thicket, with an empty crater nearby. We begin to see the life and migration of the extraterrestrial visitors.

The photographs are printed on the darker end of the tonal range, so that when light appears, it’s glowing. Large swaths of open darkness are not to be feared; there is delicacy to be found in the shadows.

Early accounts of meteorites were dismissed as superstition, as if believing in the rocks was like believing in magic. But why shouldn’t they be magic? Even if and when completely explained, are they not still a bit miraculous? In this work, there is a playful yet intentional comingling of truth and tales, with a reminder that not all tales are untrue. There is tenderness in Martin’s approach that comes from the act of careful listening- she is listening to the old tales told in small towns, she is listening to scientists, she even listens to the rocks themselves.

Dates + Events

November Pictura Kids with Emilia Martin

Saturday, November 8 | 11:00am - 12:00pm

November Gallery Walk Opening Reception: Emilia Martin

Friday, November 7 | 5:00pm - 8:00pm