Hidden Light

Cody Cobb + Raymond Thompson Jr.

Dates + Events

September Gallery Walk: Cody Cobb + Raymond Thompson Jr.

Friday, September 1 | 5:00pm - 8:00pm

September Pictura Kids: Raymond Thompson Jr.

Saturday, September 2 | 11:00am - 12:00pm

Hidden Light

Cody Cobb + Raymond Thompson Jr.

“When you are in the dark, most things feel like a discovery.” - Cody Cobb

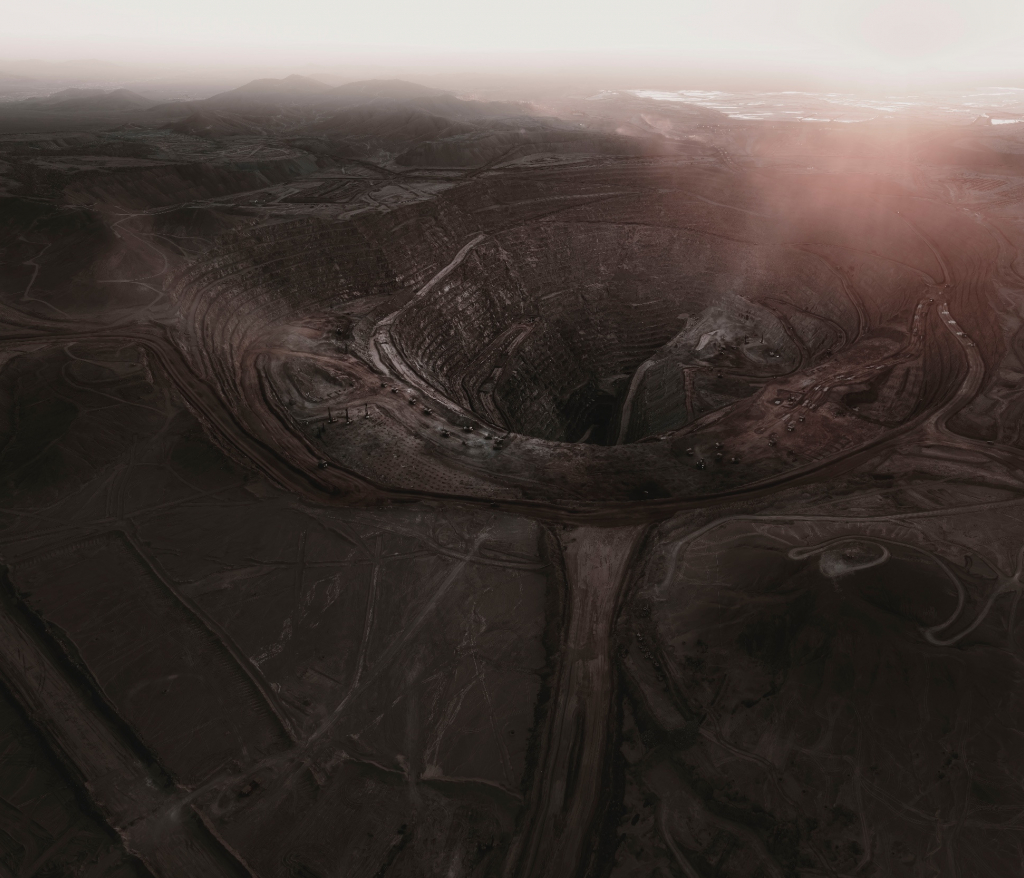

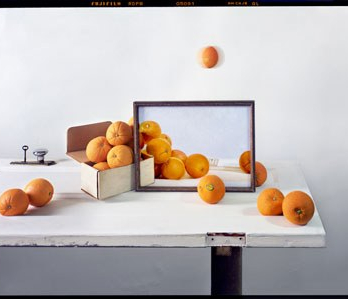

Hidden Light presents two artists who use the tools of photography to reveal color that might otherwise be unseen. In the process of applying light to landforms, pixels, and paper, they draw out brilliance from within, making it visible for us. Cody Cobb shines ultraviolet radiation into the darkness to reveal strange luminescence in the American wilderness. Raymond Thompson Jr. works directly with the sun to make lumen prints of the body, obscuring the human form in celestial darkness. The show observes surprisingly intimate qualities in the land, and explores the body as its own kind of hidden landscape.

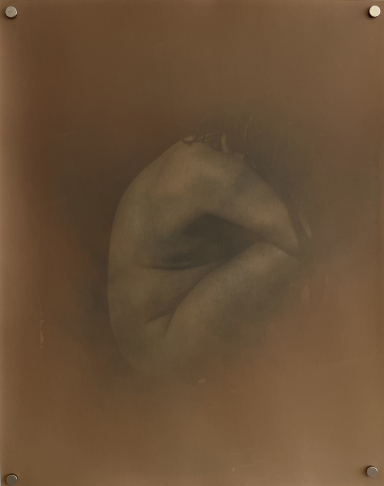

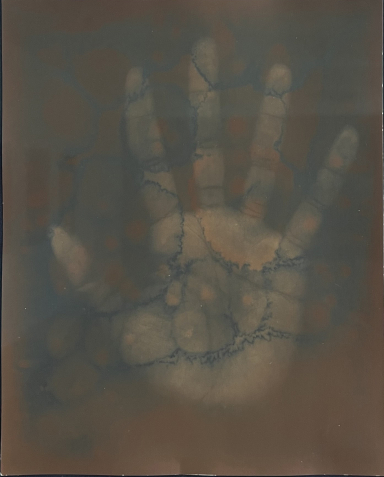

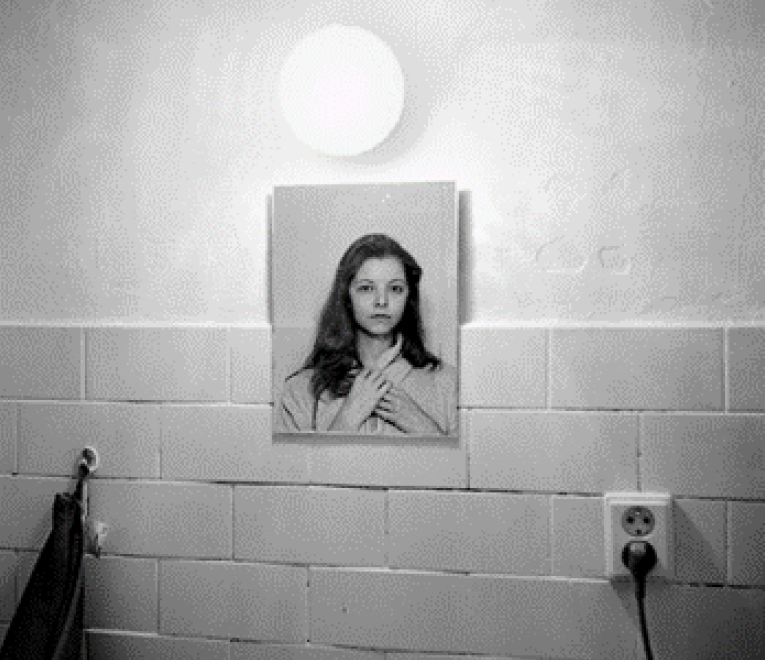

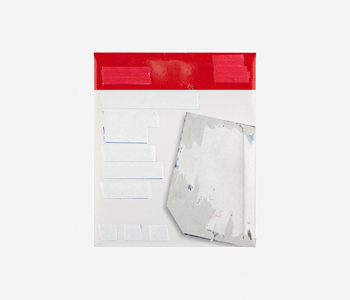

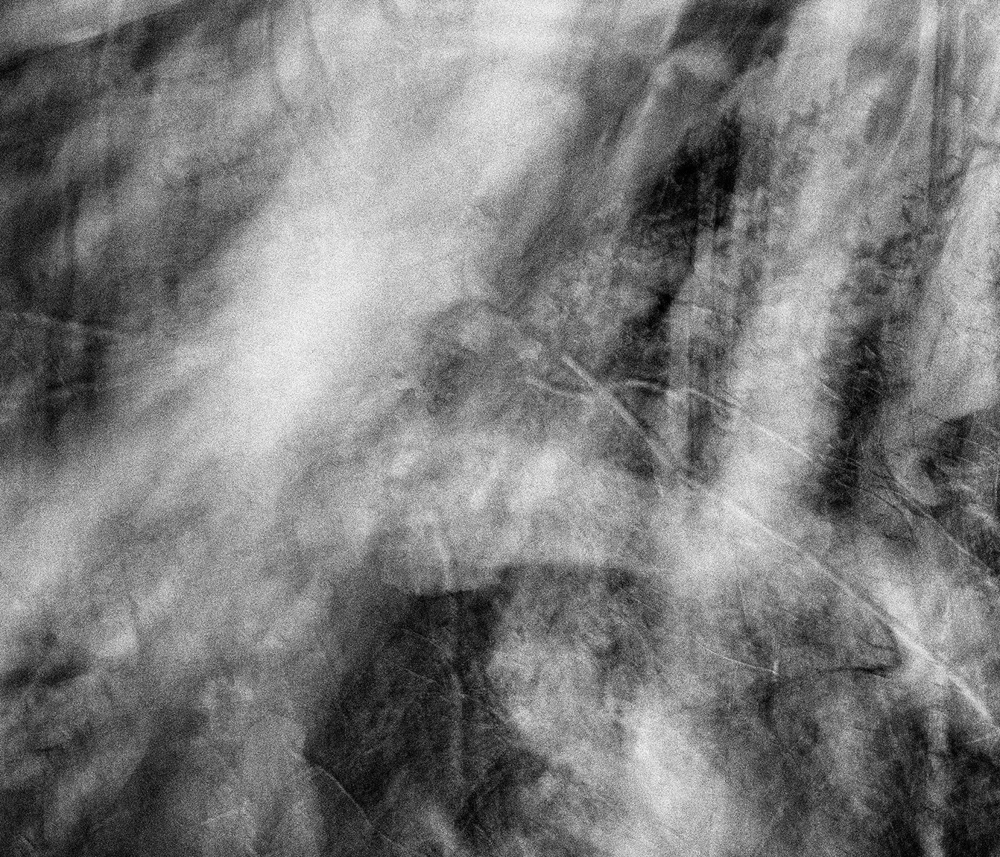

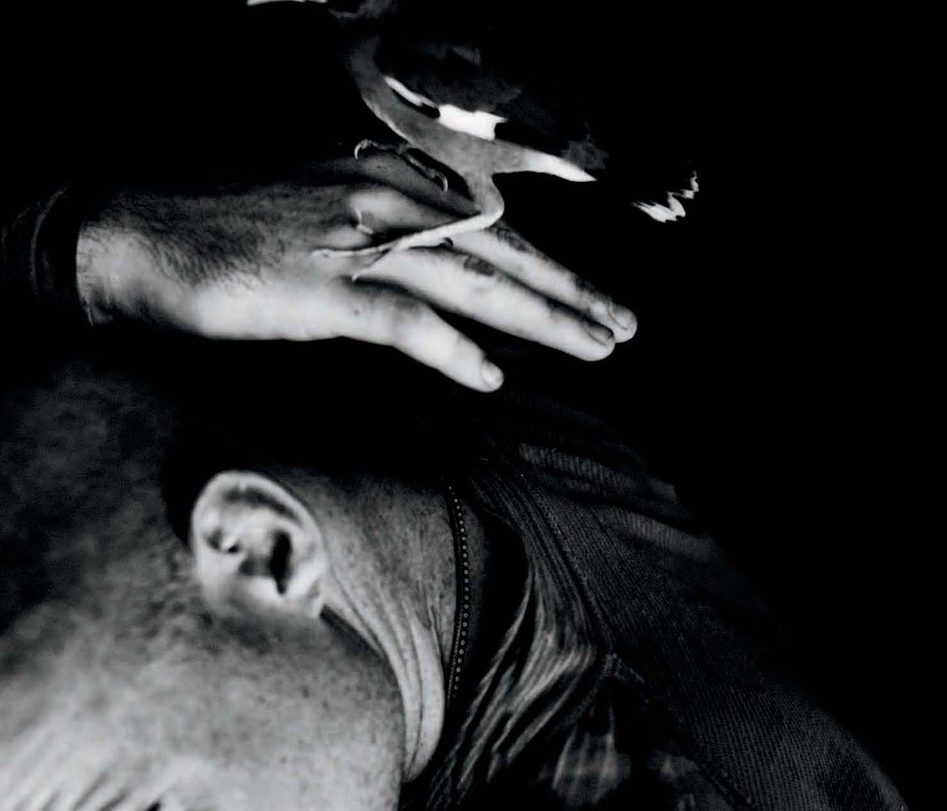

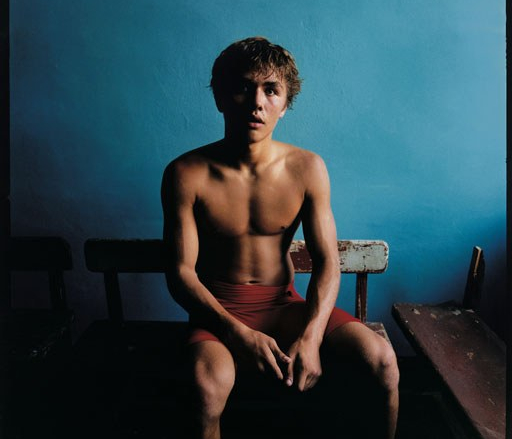

Thompson’s series, Playing In the Dark, is displayed in two ways, and both presentations conceal his figure differently. Lumen prints flatten the tonal range, so that the form and negative space begin to blend together. These delicate prints are intimate and somewhat inscrutable, soft brown and selenium tones reclaiming shades of subtlety from the history of the white gaze. The original prints have also been scanned and allowed to take on vibrant colors in the process, and then produced again as inkjet prints. In these, we swim through pools of gemlike color to seek out the body.

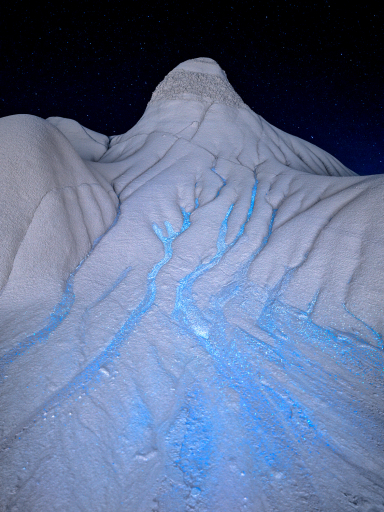

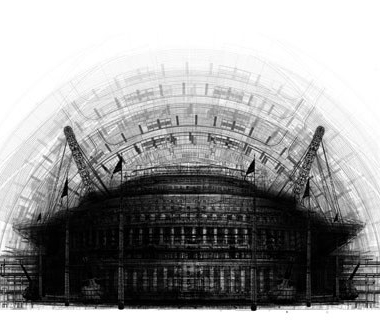

Being in the dark and without visual sensory input can bring a new kind of clarity. What new things are seen in the darkness? What previously unnoticed details come into focus when the whole is not entirely illuminated? In Spectral, Cobb follows this question to startling effect. In a red canyon, the powder blue phosphorescent glow of the water shows it as a precious and extraordinary substance. The stream leads to the bush like a blood line, imbuing it with life. The only reason we get to see what these landscapes look like at night is because Cobb has brightened them, moving a handheld lightsource over the land’s contours during a long exposure. Like an airport marshall, he signals our attention towards the hidden delight of bioluminescence.

Cobb and Thompson disrupt our practiced way of seeing by removing memory colors from their images. Memory colors are the color a beholder considers to be characteristic for an object. Two of the most common things that hold memory color are sky and skin, and these are often used by photographers to establish a sense of reality in their photographs. By shifting the colors we expect, Thompson and Cobb clear the path of our built-in assumptions and default ways of seeing, making space for a new type of vision to form.

Cody Cobb | Artist Bio

Cody Cobb (b. 1984 in Shreveport, Louisiana) is a photographer based in the American West. His photographs aim to capture brief moments of stillness from the chaos of nature.

For weeks at a time, Cobb wanders the American West alone in order to fully immerse himself in seemingly untouched wilderness. This isolation allows for more sensitive observations of both the external landscape as well as the internal experience of solitude. Through subtle arrangements of light and geometry, the illusion of structure appears as a mystical visage. These portraits of the Earth’s surface are an attempt to capture an entanglement

of the observer and the observed.

Cody Cobb was named one of PDN’s 30 emerging photographers to watch in 2018 and a winner of The Royal Photographic Society’s IPE162 award as well as being a part of Photolucida’s Critical Mass Top 50. Cody’s work has also appeared in publications such as The California Sunday Magazine, WIRED Magazine, MADE Quarterly and ‘Cascadia’ by Another Place Press.

codycobb.com

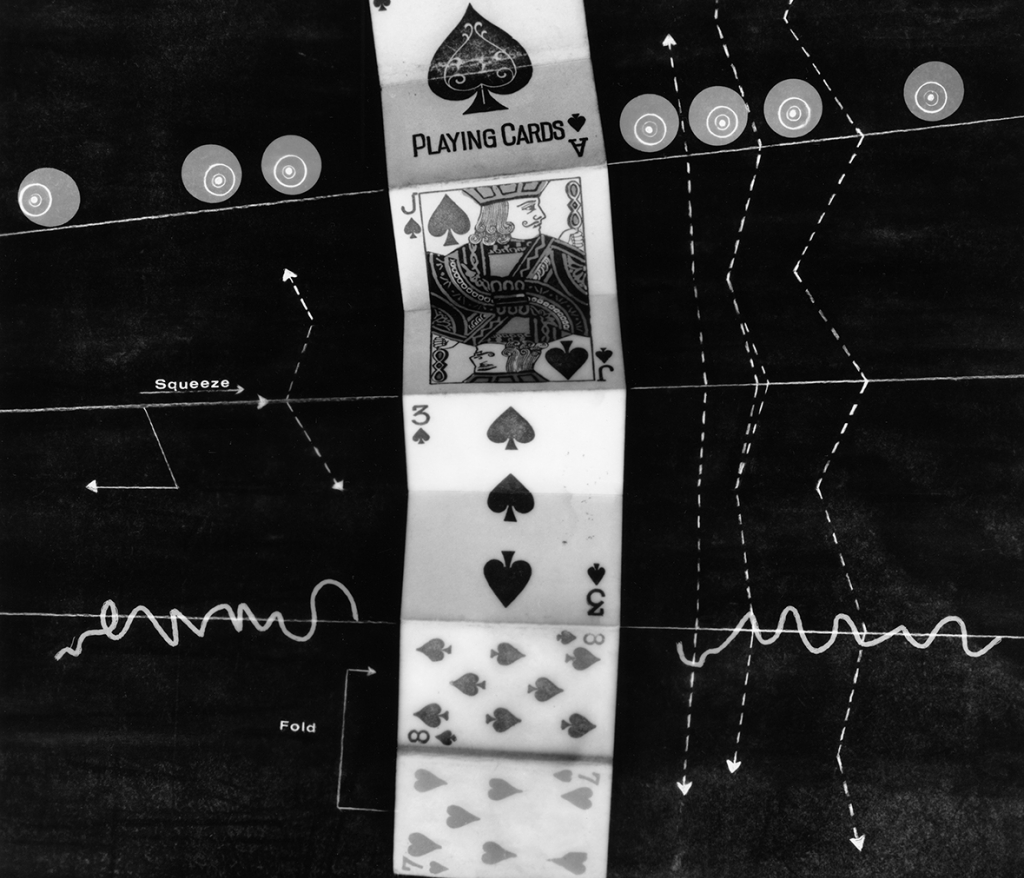

Spectral | Artist Statement

These photographs reveal a hidden luminescence in the wildernessof the American West. From collapsed lava tubes lined with microbial mats to high elevations where lichens thrive, a strange flurescence occurs when certain minerals and organic matericlas are subjected to ultraviolet radiation. This spectrum of light is invisible to humans.

A parallel world is unveiled in the night with long exposures using an ultraviolet light source. The eerie light emitted from within these once familiar surfaces transmutes the mundane into something extraterrestrial.

Raymond Thompson Jr. | Artist Bio

Raymond is an artist, educator and visual journalist based in Austin, TX. He currently works as an Assistant Professor of Photojournalism at University of Texas at Austin. He has received a MFA in Photography from West Virginia University and a MA in Journalism from the University of Texas at Austin. He also graduated from the University of Mary Washington with a BA in American Studies. He was the 2023 winner of the 1619 Aftermath Grant. He has worked as a freelance photographer for The New York Times, The Intercept, NBC News, NPR, Politico, Propublica, The Nature Conservancy, ACLU, WBEZ, Google, Merrell and the Associated Press.

raymondthompsonjr.com

Playing in the Dark | Artist Statement

I have harvested the power of the sun for my most recent series of self-portrait lumen prints, Playing in the Dark. I borrowed the title from a Toni Morrison (1931-2019) book called, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, in which she critiques the dependence of American literature on the presence of the black body. This work comments on the nature of photography as a scientific process, and the role photography has played in reinforcing America’s racial caste system. More importantly, the series asks viewers to look deeper by purposely deemphasizing my body with various dark tones and colors. My body is not easily consumed in this work. I used the lumen printing process because the way images are rendered on the surface of the prints creates a shroud that forces the viewer to investigate at close range. The series consists of silver gelatin prints split-toned with selenium.

For this series, I use a process closely related to the process in use at the birth of the medium. The images for this work are in conversation with Daguerre and Talbot with the goal of placing a metaphorical asterisk in the photography history books. The annotation would point to photography’s relation to race and racism in American culture. Christina Sharpe argues in her book, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, that a mode of “black annotation and black redaction” is needed to create a space for “ethical viewing and reading practices,” free from the traps of settler colonial violence. I intended this work to push back against the white gaze’s need for easily digestible otherness. My body became the site for a practice of “black annotation and redaction.” The series asks viewers to look deeper by purposely deemphasizing my body with various dark tones and colors. My body is not easily consumed in this work. I used the lumen printing process because the way images are rendered on the surface of the prints creates a shroud that forces the viewer to investigate at close range.

I was inspired by African American photographer Roy DeCarava’s printing technique, which focused on underexposure, soft papers, and an incredible range of dark and gray tones. DeCarava was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to complete his book, The Sweet Flypaper of Life. In this work, he focuses on everyday black life in Harlem. He purposely avoided the typically published imagery of blacks that concentrated on the extremes.

In Teju Cole’s essay, A True Picture of Black Skin, published in the book Black Futures, he argues that DeCarava’s darkroom printing palette reverses the power structures associated with the white gaze in photography. “The viewer’s eye might at first protest, seeking more conventional contrasts, wanting more obvious lighting. But, gradually, there comes an acceptance of the photograph and its subtle implications: that there’s more there than we might think in the first place, but also that when we are looking at others, we might come to the understanding that they don’t have to give themselves up to us. They are allowed to stay in the shadows if they wish,” Cole writes. Cole connects DeCarava’s work to philosopher Edouard Glissant’s thinking that surrounds the word “opacity.” In his writing, he claimed a space for the rights of minorities not to be defined by others’ definitions and the right to be misunderstood if they wanted. “Glissant sought to defend the opacity, obscurity, and inscrutability of Caribbean Blacks and other marginalized peoples. External pressures insisted on everything being illuminated, simplified, and explained. Glissant’s response: No.” This work swims in the shadows and asks the viewer to look deeper.

Hidden Light

Cody Cobb + Raymond Thompson Jr.

“When you are in the dark, most things feel like a discovery.” - Cody Cobb

Hidden Light presents two artists who use the tools of photography to reveal color that might otherwise be unseen. In the process of applying light to landforms, pixels, and paper, they draw out brilliance from within, making it visible for us. Cody Cobb shines ultraviolet radiation into the darkness to reveal strange luminescence in the American wilderness. Raymond Thompson Jr. works directly with the sun to make lumen prints of the body, obscuring the human form in celestial darkness. The show observes surprisingly intimate qualities in the land, and explores the body as its own kind of hidden landscape.

Thompson’s series, Playing In the Dark, is displayed in two ways, and both presentations conceal his figure differently. Lumen prints flatten the tonal range, so that the form and negative space begin to blend together. These delicate prints are intimate and somewhat inscrutable, soft brown and selenium tones reclaiming shades of subtlety from the history of the white gaze. The original prints have also been scanned and allowed to take on vibrant colors in the process, and then produced again as inkjet prints. In these, we swim through pools of gemlike color to seek out the body.

Being in the dark and without visual sensory input can bring a new kind of clarity. What new things are seen in the darkness? What previously unnoticed details come into focus when the whole is not entirely illuminated? In Spectral, Cobb follows this question to startling effect. In a red canyon, the powder blue phosphorescent glow of the water shows it as a precious and extraordinary substance. The stream leads to the bush like a blood line, imbuing it with life. The only reason we get to see what these landscapes look like at night is because Cobb has brightened them, moving a handheld lightsource over the land’s contours during a long exposure. Like an airport marshall, he signals our attention towards the hidden delight of bioluminescence.

Cobb and Thompson disrupt our practiced way of seeing by removing memory colors from their images. Memory colors are the color a beholder considers to be characteristic for an object. Two of the most common things that hold memory color are sky and skin, and these are often used by photographers to establish a sense of reality in their photographs. By shifting the colors we expect, Thompson and Cobb clear the path of our built-in assumptions and default ways of seeing, making space for a new type of vision to form.

Cody Cobb | Artist Bio

Cody Cobb (b. 1984 in Shreveport, Louisiana) is a photographer based in the American West. His photographs aim to capture brief moments of stillness from the chaos of nature.

For weeks at a time, Cobb wanders the American West alone in order to fully immerse himself in seemingly untouched wilderness. This isolation allows for more sensitive observations of both the external landscape as well as the internal experience of solitude. Through subtle arrangements of light and geometry, the illusion of structure appears as a mystical visage. These portraits of the Earth’s surface are an attempt to capture an entanglement

of the observer and the observed.

Cody Cobb was named one of PDN’s 30 emerging photographers to watch in 2018 and a winner of The Royal Photographic Society’s IPE162 award as well as being a part of Photolucida’s Critical Mass Top 50. Cody’s work has also appeared in publications such as The California Sunday Magazine, WIRED Magazine, MADE Quarterly and ‘Cascadia’ by Another Place Press.

codycobb.com

Spectral | Artist Statement

These photographs reveal a hidden luminescence in the wildernessof the American West. From collapsed lava tubes lined with microbial mats to high elevations where lichens thrive, a strange flurescence occurs when certain minerals and organic matericlas are subjected to ultraviolet radiation. This spectrum of light is invisible to humans.

A parallel world is unveiled in the night with long exposures using an ultraviolet light source. The eerie light emitted from within these once familiar surfaces transmutes the mundane into something extraterrestrial.

Raymond Thompson Jr. | Artist Bio

Raymond is an artist, educator and visual journalist based in Austin, TX. He currently works as an Assistant Professor of Photojournalism at University of Texas at Austin. He has received a MFA in Photography from West Virginia University and a MA in Journalism from the University of Texas at Austin. He also graduated from the University of Mary Washington with a BA in American Studies. He was the 2023 winner of the 1619 Aftermath Grant. He has worked as a freelance photographer for The New York Times, The Intercept, NBC News, NPR, Politico, Propublica, The Nature Conservancy, ACLU, WBEZ, Google, Merrell and the Associated Press.

raymondthompsonjr.com

Playing in the Dark | Artist Statement

I have harvested the power of the sun for my most recent series of self-portrait lumen prints, Playing in the Dark. I borrowed the title from a Toni Morrison (1931-2019) book called, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, in which she critiques the dependence of American literature on the presence of the black body. This work comments on the nature of photography as a scientific process, and the role photography has played in reinforcing America’s racial caste system. More importantly, the series asks viewers to look deeper by purposely deemphasizing my body with various dark tones and colors. My body is not easily consumed in this work. I used the lumen printing process because the way images are rendered on the surface of the prints creates a shroud that forces the viewer to investigate at close range. The series consists of silver gelatin prints split-toned with selenium.

For this series, I use a process closely related to the process in use at the birth of the medium. The images for this work are in conversation with Daguerre and Talbot with the goal of placing a metaphorical asterisk in the photography history books. The annotation would point to photography’s relation to race and racism in American culture. Christina Sharpe argues in her book, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, that a mode of “black annotation and black redaction” is needed to create a space for “ethical viewing and reading practices,” free from the traps of settler colonial violence. I intended this work to push back against the white gaze’s need for easily digestible otherness. My body became the site for a practice of “black annotation and redaction.” The series asks viewers to look deeper by purposely deemphasizing my body with various dark tones and colors. My body is not easily consumed in this work. I used the lumen printing process because the way images are rendered on the surface of the prints creates a shroud that forces the viewer to investigate at close range.

I was inspired by African American photographer Roy DeCarava’s printing technique, which focused on underexposure, soft papers, and an incredible range of dark and gray tones. DeCarava was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to complete his book, The Sweet Flypaper of Life. In this work, he focuses on everyday black life in Harlem. He purposely avoided the typically published imagery of blacks that concentrated on the extremes.

In Teju Cole’s essay, A True Picture of Black Skin, published in the book Black Futures, he argues that DeCarava’s darkroom printing palette reverses the power structures associated with the white gaze in photography. “The viewer’s eye might at first protest, seeking more conventional contrasts, wanting more obvious lighting. But, gradually, there comes an acceptance of the photograph and its subtle implications: that there’s more there than we might think in the first place, but also that when we are looking at others, we might come to the understanding that they don’t have to give themselves up to us. They are allowed to stay in the shadows if they wish,” Cole writes. Cole connects DeCarava’s work to philosopher Edouard Glissant’s thinking that surrounds the word “opacity.” In his writing, he claimed a space for the rights of minorities not to be defined by others’ definitions and the right to be misunderstood if they wanted. “Glissant sought to defend the opacity, obscurity, and inscrutability of Caribbean Blacks and other marginalized peoples. External pressures insisted on everything being illuminated, simplified, and explained. Glissant’s response: No.” This work swims in the shadows and asks the viewer to look deeper.

Dates + Events

September Gallery Walk: Cody Cobb + Raymond Thompson Jr.

Friday, September 1 | 5:00pm - 8:00pm

September Pictura Kids: Raymond Thompson Jr.

Saturday, September 2 | 11:00am - 12:00pm